Baking soda cooks the beans faster?

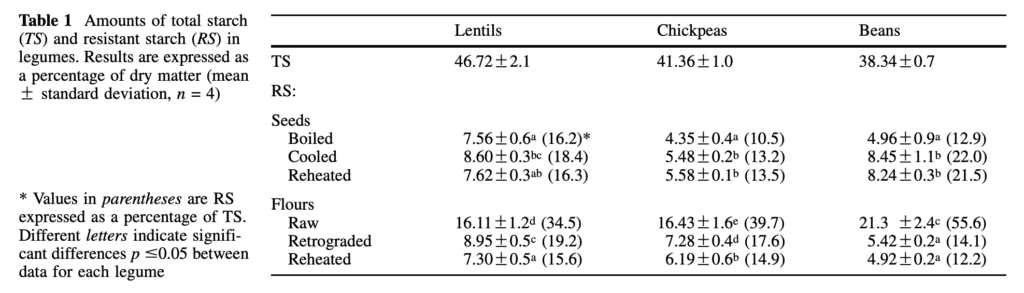

These seeds are salubrious, rich in vitamins, minerals, protein, and starch, majorly a form of starch called resistant starch, which according to much research is proven to be good for our gut microbiota. And as discussed in one of the previous blogs (here), starch is the source of most life on earth. And beans contain a lot of resistant starch (Table 1). Resistant Starch is defined as the fraction of dietary starch, which is not digested in the small intestine. It is measured chemically as the difference between total starch (TS) obtained from homogenized and chemically treated samples and the sum of Rapidly Digestible Starch (RDS) and Slowly Digestible Starch (SDS), generated from non-homogenized food samples by enzyme digestion (M.G. Sajilata et al, 2006).

RS = TS – (RDS + SDS)

SOURCE: García-Alonso et al, 1998.

SOURCE: García-Alonso et al, 1998.

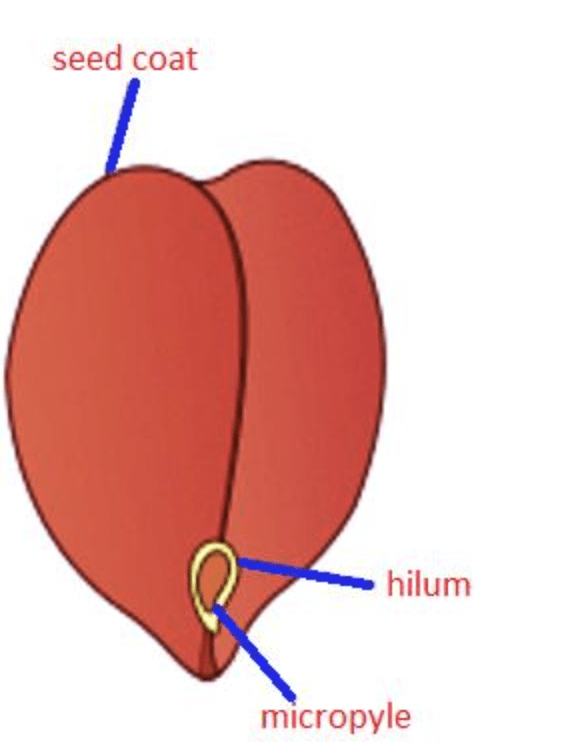

And as they are very low in water content, dry beans last a very long time; they are not susceptible to attack by bacteria, mold, or fungi. Thus, they offer a source of healthy food that is cheap, readily available, and can be stored for years without food safety problems. And if we look at this aspect from another perspective, this low content of water is what makes them a pain in the neck to cook, they take forever! The step in cooking dry beans which is slower is the absorption of water into the beans, which can only enter through a very small opening called the micropyle (see Figure 1), to turn them soft, as well as gelatinize the starch that must be cooked in order to be digestible. So to cut down on the cooking time we soak them. Also, Guy Crosby, in his book The Science of Good Cooking, recommends brining the beans at a low salt concentration before cooking, during which the sodium ions slowly replace the calcium ions, which strengthens the pectin and pectin strengthens the cell walls in the beans. And this natural pectin produces skin on the outside of the dry bean which can be difficult to soften and hence expand while cooking. This skin can eventually burst when the inside of the beans becomes over-cooked. Exchanging sodium for calcium ions during brining weakens the pectin so the skins become more flexible and can expand without bursting as the interiors cook to a soft creamy texture. So all in all, brining does two things, a) reduce the cooking time by soaking and b) “softens” the pectin to have a more malleable skin and the beans don’t burst.

But the question or the lore, in this case, is why our mothers or grandmothers or anyone tell us to add baking soda while cooking the beans? Well, the popular belief this time is rational. Baking soda does two things: first, it provides sodium ions which function, in the same way, as explained above, and second, it breaks down pectin (which is a very long chain polysaccharide) into smaller molecules that are easier to cook and cut down the cooking time radically.

References

García-Alonso, A., Goni, I., & Saura-Calixto, F. (1998). Resistant starch and potential glycaemic index of raw and cooked legumes (lentils, chickpeas and beans). Zeitschrift für Lebensmitteluntersuchung und-Forschung A, 206(4), 284-287.