Why do some people hate coriander?

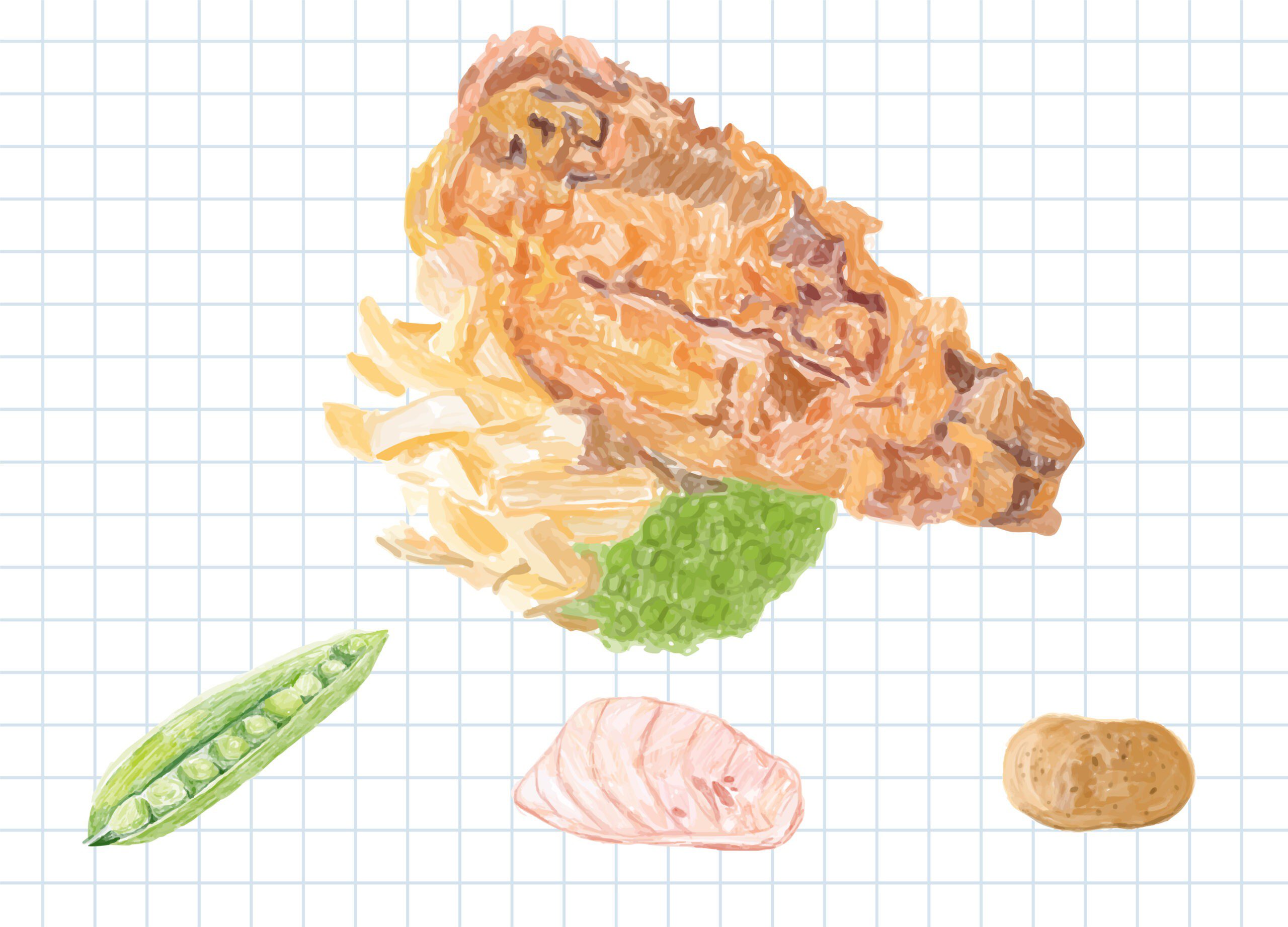

Most people can’t help but be close-minded or afraid when trying new experiences. In the case of food, people’s close-mindedness peaks when trying new flavors. This phenomenon of fearing new flavors has a name: neophobia. This feeling has its explanations, however, it may also appear around foods that are closer to us than we think. This is the case with cilantro. Even though Coriandrum sativum (cilantro, coriander, or Chinese parsley) is native to the Mediterranean coast and central Asia, with a significant presence in the cosmetic, perfume, and pharmaceutical industries, part of the western population still find it as a foreign or strange ingredient, not much seen on their daily diet.

Beyond the fear of the unknown, there is a scientific reason why some foods taste different to different people, as is the case with cilantro. The taste and smell of some food compounds may vary depending on each individual’s genetic makeup, hence we can’t blame those who weren’t lucky enough to be born with the genetic sequence that allows us to appreciate cilantro. As a result, those who do not present a specific sequence may perceive cilantro compounds to have a tart, lemon, or lime-like flavor, while those who present it may find coriander leaves to taste like bath soap.

As a matter of fact, coriander originated from a Greek word, koris, which means bad-smelling bug and, although the proportion of people who dislike cilantro varies widely due to differences in cultural and social factors, such as frequency of exposure, a recent study revealed that there is a genetic component to cilantro taste perception that makes it unpleasant for some people. This means that specific genetic variants in our olfactory receptors allow us to perceive concrete flavors and aromas. So that those who perceive the soapy taste of cilantro have the olfactory receptors responsible for recognizing the volatile compounds related to soap.

Likewise, the olfactory receptor neurons (ORNs) contain about 400 functional genes in the human genome (the complete set of DNA in an organism). Each one binds to a group of chemicals enabling us to recognize specific odorants or tastants. Most individuals who despise coriander present a common olfactory receptor gene called OR6A2 (Eriksson, 2012), which absorbs the aldehyde chemicals (mostly unsaturated n-aldehydes volatile oils) that give cilantro its distinctive aroma and so they associate it with a soapy smell or taste. Those who do not like the taste of cilantro are sensitive to unsaturated aldehydes contained in other foods, while those unable to detect these aromatic chemicals find cilantro pleasant.

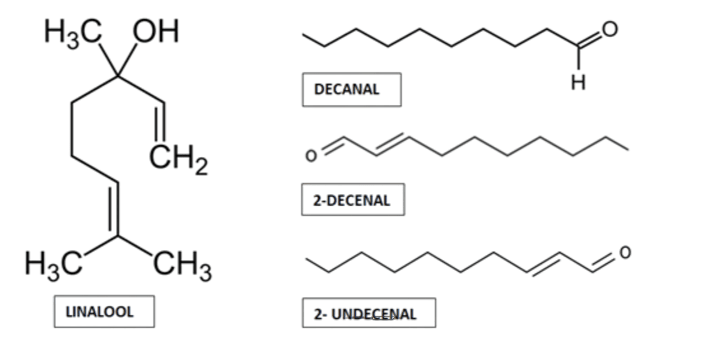

Moreover, the aldehydes present in cilantro are also found in many soaps, detergents, and lotions, as well as linalool, which is an alcohol that is present in cilantro’s composition as well as perfumed hygiene products. The primary aldehydes present in cilantro are decanal, 2-decenal, and 2-undecenal, all of them recognizable by the olfactory receptors of individuals that possess the OR6A2 gene (Figure 1). Although the olfactory receptor gene 0R6A2 has been proven to pass hereditarily it is also found to have low heritability. As a result, parental genes do not always determine its presence. Therefore, it can be modified by a change of habits, like including cilantro in the daily diet more often. This is explained through epigenetics (the study of how your behaviors and environment can cause changes that affect the way your genes work).

Figure 1: Molecules responsible for cilantro’s taste perception (Calo, 2015)

Figure 1: Molecules responsible for cilantro’s taste perception (Calo, 2015)

One curious example related to this case could be that the food preference of a mother can be transmitted to the fetus in utero. For instance, if the mother doesn’t like cilantro but she eats it during pregnancy, it is more likely that the child will like cilantro in the future because the child “learns” to get used to its taste.

So if you are one of those who think that cilantro messes up a meal, don’t worry, you are not alone! You are always on time to learn to like it, don’t be afraid to play with new flavors and aromas and enjoy the ride, because as Harold Mcgee said; “Smell is something very intimate. The receptor must bind to a molecule, for a brief moment, to send a message to the brain. So that, for a brief moment, the smell is part of you”.

References used:

- Calo J. R., Crandall P. G., O’Bryan C. A., Ricke S. C. (2015). Essential oils as antimicrobials in food systems – a review. Food Control 54 111–119. 10.1016/j.foodcont.2014.12.040

- Eriksson N., Wu S., Do C.B., Kiefer A.K., Tung J.Y., Mountain J.L., Hinds D.A., Francke U. (2012). A genetic variant near olfactory receptor genes influences cilantro preference. Flavour. 1:22. DOI: 10.1186/2044-7248-1-22.

- Zohary, D., Hopf, M., & Weiss, E. (2012). Domestication of Plants in the Old World: The Origin and Spread of Domesticated Plants in Southwest Asia, Europe, and the Mediterranean Basin (4th ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:osobl/9780199549061.001.0001