“The decadent seafood feast we associate with the word paella is worlds away from the original dish”

Consider the gastronomy of Spain and perhaps the first thing that comes to mind is paella, the quintessentially Spanish rice dish cooked in an enormous pan over an open fire. A dish of steaming golden rice with king prawns placed artfully on top, mussels nestled in between each one, and, being Spanish, chorizo, of course. In Valencia, the acknowledged home of paella, Sunday is the day to enjoy it. Although, when you sit at a paellería by Valencia’s Malvarrosa beach waiting for your food to arrive, you may be surprised to see, not prawns, but a snail or two, and meat on the bone, rabbit meat for a truly authentic experience. Besides, seafood wouldn’t be seen dead crossing paths with chorizo. Surf ‘n’ turf just doesn’t exist in Spain. Other typical ingredients in a paella that might come as a surprise are white beans, maybe artichokes, pork, and always saffron to give it that tempting warmth. The decadent seafood feast we associate with the word paella is worlds away from the original dish however, whose existence was not lent to extravagance, but necessity and resourcefulness, and whose principal ingredient – rice – is largely ignored but rich in history.

Paella was first eaten in the Valencian paddy fields with locally sourced ingredients the farmers could forage, cooked over a log fire alongside the rice they had grown, and named after the shallow frying pan the ingredients were cooked in. Not quite the hedonistic holiday meal of today, nor the Mediterranean coastal backdrop you’d expect. But as we get carried away debating what is and isn’t in a paella, we forget that it all boils down to the rice – the core ingredient. In “Arròs amb fesols i naps” by Valencian poet Llorente, the esteem for rice is evident, as one labourer asks another:

“If you were the king of Spain

what would you have for lunch today?”

Raising his forehead full of wrinkles,

and releasing his ready tongue,

he answered him, “What, you don’t know?

What a silly question!

Rice with beans and turnips!”

“And you?” added the elder.

The little one sighed

and, shaking off the sweat,

he replied, “What should I say,

when you have already said the best thing?”Teodoro Llorente, around 1892

(Originally in Valencian)

But if we look a little bit closer at the rice plains surrounding these hungry farmers, we see that the seed of this ubiquitous dish was first planted, literally, at the start of a much earlier era, in a civilisation that we wouldn’t recognise today.

There was a time when rice was unheard of and these fields didn’t exist at all; it was the introduction of this vital crop from overseas to these lands that allowed paella to be born, and consequently introduced the grain to the rest of Europe. For rice to grow, the right conditions are necessary, and with its marshy habitat and constant thirst, the abundance and control of water is vital for it to flourish. This can have deadly consequences, as we’ll see later, yet it’s hard to envisage these eastern Spanish terrains without the marshes spreading far and wide, their intricate channels feeding the land around them, reeds swaying in the breeze, an egret purveying the ecosystem by tentatively wading the water in search of insects.

“The Arabs’ upgraded mosaic of floodgates, weirs, channels, and dams formed the nation’s veins, and the city of Valencia the heart”

When the Moors, a mix of Berbers and Islamic Arabs at the time, started arriving in the south of Spain from around 700 AD, the nation of Al-Andalus was formed and the country began to prosper. Some of these emigrants reached Valencia and stayed. The climate, terrain, and lakes here were ideal for cultivating crops, and most importantly rice, but first came some vital changes. The newcomers set about applying their agricultural knowledge to the land around them, creating complex irrigation systems that still remain today. From the river Turia, funnels of water travel to thousands of fields, sharing the water equally between them and preventing water shortages. Irrigation as an idea admittedly doesn’t conjure up much excitement, but if it weren’t for these compounded water systems, rice wouldn’t be so prevalent in European gastronomy today, and those hungry Valencia farmers wouldn’t have come up with this idea to satisfy the stomach.

“There was a time when rice was unheard of and these fields didn’t exist”

With water taking centre stage, the Arabs’ upgraded mosaic of floodgates, weirs, channels, and dams formed the nation’s veins, and the city of Valencia the heart. To this day, this advanced irrigation system allows crops that would not normally grow side by side to coexist. Aubergines, peaches, and citrus fruits, to name a few, became abundant, and these farming methods – used even now – allowed the Valencian plains to transform into a rich provider of food. Water is life and a tool for growth; one the Moors, coming from water-stricken lands, knew only too well how to harness.

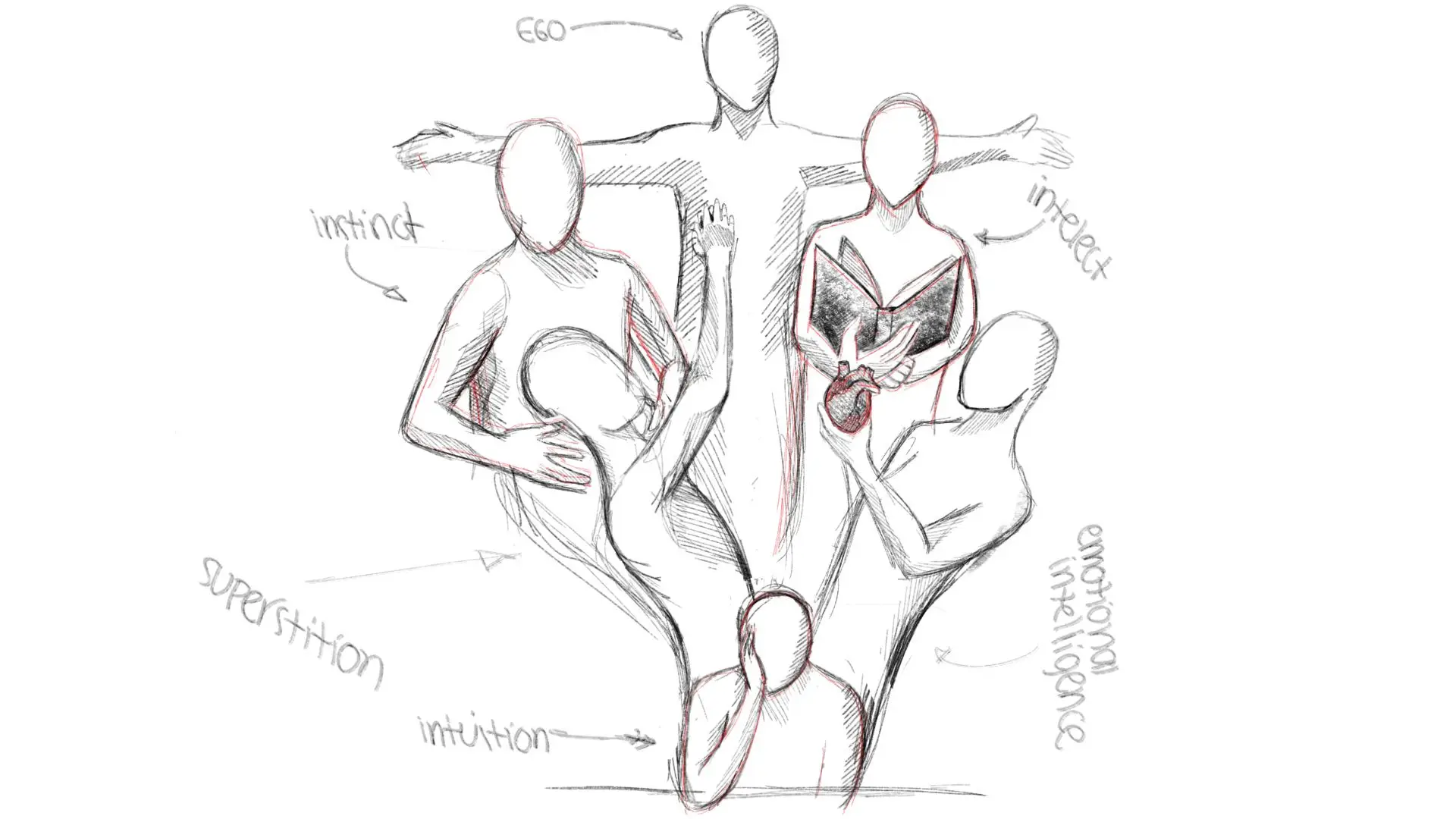

Where the Moors themselves learned these complex farming methods is not clear, but they undoubtedly hark back to Asia – the birthplace of rice – as does the word itself – ar-uzz (أرز) in Arabic, and consequently arroz in Spanish – with roots in Sanskrit or Tamil. If we go back far enough, to a time before rice had reached the Middle East, before institutional religion had moved in, we find ourselves on an island in the Indian Ocean called Java. Here in Indonesia, the legend of the Goddess of Rice – a woman whose father, a god, asks for her hand in marriage – raises the humble crop to even headier heights. She accepts to marry him on one condition: that he bring her “food that one never gets tired of, clothing that never wears out, and musical instruments that make sound without being played.” Rice without doubt remains a staple that doesn’t just stretch over countries, but continents – from the floodplains in Spain to those in Indonesia, it is a shared sustenance so ordinary yet miraculous in its power to provide so much.

The father of our mythical goddess fails to meet her conditions, and although there are various renditions of the Indonesian myth, unsurprisingly it doesn’t end well for the woman in any of them, as she is tragically killed and her body is buried in a field. However, once she is laid to rest, a curious thing happens and it is this that gives her the name Dewi Sri – Goddess of Rice. Forty days after her death, plants start to sprout from her body, blades of Oryza grass spring from her navel, and the seeds of this plant are what we call rice; the food that one – and according to Llorent’s poem, even the King of Spain himself – ‘never gets tired of’.

Indonesia is not the only Asian country to possess an ancient female deity with rice as her emblem and strength. In Thailand, Mae Phosop is the mother of rice, and her pregnancy is the gift of harvest. Both women loom over the lands as life-giving forces that call for respect, their fertility, and their power; they serve as the protectors of hunger and therefore dictate life itself. Rice is not just another ingredient in a paella dish, but a way of life.

Traveling back rather forward to the Moors in Al-Andalus once again, we see they ate rice slightly differently from how it is eaten in Spain today. The Arab civilians would cook rice in goat’s milk with lashings of honey, a sprinkle of nutmeg, and almonds crushed on top. The first known rice dish in Spain, Manjer Blanc, was practically rice pudding.

In one of the earliest written records of ‘Spanish’ gastronomy, Libre de Sent Soví, the presence of rice, as well as saffron, cinnamon, and cane sugar are telltale signs of the strong Arabic influence on the evolving gastronomical sphere in Spain.

There is something else that the Moors brought with them upon their arrival in Spain that still exists today, and arguably without it, the paella we know so well wouldn’t exist; and that is democracy. Thanks to the Arabs and their agricultural feats, the oldest democratic body in the world still runs in Valencia today and functions to ensure fairness and equal distribution of water to farmers. Every Thursday in Valencia city, just outside the cathedral, watch a democratic process of dispute and decision-making that is over 1000 years old take place in front of your eyes, eight simple wooden chairs in a circle marking its place. No paper, no pen, just one person’s word against another’s. This is the Tribunal de les Aigües, the water tribunal that has been independently handling all things water since the Arabs were around. Just like the Asian goddesses long before them, these eight elected farmers are the Guardians of water, the Purveyors of crops, and the Guarantors of rice on the table.

Why at the entrance of the cathedral and not inside? And why Thursday? Before Christianity took hold once again in Spain, the mosque was the meeting point for such democratic discussions, but when the mosques were replaced with churches, the Muslims who had paved the way for this open discourse were now unable to enter. Yet it seems the Islamic day of rest and prayer prevailed, as the weekly meetings still take place every Thursday, the day before holy Jumu’ah.

“Rice offers the gift of abundance – and in this case, it came in monetary form – yet due to human greed and ignorance, also at the cost of lives”

Jumping 1000 years ahead to the 18th century – with Al-Andalus long dissolved, and the last Muslims expelled from the country during the Expulsion of the Moriscos some three hundred years before – there comes a stark reminder of how the role of rice – a key part of civilisation and daily life in the region since the Moors had ruled – as a lifeline can only go so far if not respected. As the population grew, crop yields increased in order to provide enough food; before then, Valencia had depended on imports from neighbouring regions such as Aragon and La Mancha. Authorities relaxed rules on rice cultivation allowing farmers to grow more freely – rice fields became denser and edged closer and closer to populated areas. With the now old Arab irrigation systems still in place, but perhaps less strictly abided by, a subtle but lethal problem began to fester.

Lush grassy areas allow ecosystems to thrive, yet where there is stagnant water, there are insects, and more notably mosquitoes. As the marshy plains expanded around and beyond the Albufera lagoon in Valencia, the number of mosquitoes grew and people started getting ill. A ‘tropical’ mosquito species was later identified as the killer, and malaria its poison. Many labourers worked all day in the fields and lived right next to the mosquito breeding grounds, marking the profession of a rice farmer at the time a perilous job. In the towns by the Turia riverbanks, the malaria epidemic got so bad that in some places there were more people dying than being born; malaria developed into an endemic disease and rice was to blame.

From being the beating heart of civilization, rice had now led to its demise. We’ve come full circle: Dewi Sri’s sacrifice as the gift of rice to the world now leads us back down the path of death, this time with only mosquitoes – the carriers of death – reaping the benefits of fertility, and the farmers the noble sacrifice. Rice had blood on its hands, and it continued to for far too long. Although people were aware of the dangers, rice cultivation and production persisted, as it was such a lucrative business for the wealthy landowners, and workers couldn’t afford to lose their jobs. As a ‘provider’, rice offers the gift of abundance – and in this case, it came in monetary form – yet due to human greed and ignorance, also at the cost of lives. It was only when the social costs started to have such a drastic impact in the 19th century that rice cultivation was centralised and strictly regulated to only a few large producers. Malaria cases started to decline until eventually becoming obsolete.

“The path rice has taken from Asia, to North Africa, to Spain seems to take us back once again to the reason for its very existence – water”

Nowadays Spain remains a cultivator of rice, primarily the short grain variety with two types protected under the Denomination of Origin status – Bomba and Calasparra. This rice is especially good for paella and other Spanish dishes due to its low starch content and – once again returning to rice and its incessant thirst – the ability to absorb a lot of water without losing form; as you cook paella over a long flame, the rice maintains its bite. Bomba rice also leaves that delectable crispy almost burned part of the paella at the bottom of the pan – el socarrat, a sticky glazed creation so highly prized it has its own name in Valencian. Valencian water itself is also greatly revered when cooking paella – locals have been known to carry bottles of it when traveling to foreign lands, claiming the hard water is the secret to the perfect paella. The path rice has taken from Asia, to North Africa, to Spain seems to take us back once again to the reason for its very existence – water.

Spain may not consume as much rice as it used to, and very little when compared to countries in Asia and Latin America, yet this basic commodity provides 20% of the world’s dietary energy source, which paella plays an albeit minor role in; and the number of hungry mouths is only going to increase. As we scramble to find ways to feed future generations – with two billion more humans on earth by 2050 – without destroying the planet further than we already have, we could take a leaf out of the Arabs’ agricultural manual for sustainable farming, and one from the goddesses’ as they command respect for the earth.

Some argue the solution is Golden Rice; not the saffron-infused amber rice we find in paella, but the genetically modified rice variety that was created a few decades ago. With resistance to flooding and drought, its relationship with water is less demanding, as it submits to ever-increasing extreme weather conditions, and it is also high in vitamin A – a micro-nutrient vital to child development. Despite all of that, it’s been more than 20 years, and it was only in 2021 that the first country, the Philippines, approved Golden Rice for cultivation. Why it has taken so long for genetically modified rice to take hold is fiercely debated. There is undoubtedly skepticism and objection towards GMOs in general, but others argue Golden Rice is an idealistic crusade with its promise of solving the world’s problem of hunger a hollow one. Perhaps rice’s almost holy properties and life-giving forces are the issues; it’s untouchable and attempting to alter it is fruitless.

Rice is the world’s protagonist in quotidian cooking, and whether this changes is up to us. What we know is that rice needs plenty of water, and as the venerable Valencian Guardians of water know too well, water is a precious substance that is only becoming more scarce.

Paella made in Valencia is meant to be the best in the world due to the local water, yet rice started out as the contrary – an import from overseas; a gift with a past that continues to take on ever-changing forms. Each spoon dive amongst friends and family into the sizzling pan is a reminder of those humble farmers working in the paddy fields, the moors building their canals, Valencian chefs proudly clasping their bottled water, and the circle of eight men who sit outside the cathedral on their quest for fairness. And if we pause for a moment, we can see Dewi Sri in the distant marshes, her long neck swaying in the breeze as she continues to provide a lifeline; a substance whose arrogant demand for water is forgiven due to its gift of providing sustenance to many.

References:

- Cavanilles, A. J. (1795). Observaciones sobre la Historia Natural, Geografia, Agricultura, Poblacion y Frutis del Reyno de Valencia. La Imprenta Real.

- Heringa, R. (1997). Dewi Sri in Village Garb: Fertility, Myth, and Ritual in Northeast Java. Asian Folklore Studies, 56(2), 355–377. https://doi.org/10.2307/1178731

- Kellogg, E.A. (2009). The Evolutionary History of Ehrhartoideae, Oryzeae, and Oryza . Rice 2, 1–14 . https://doi.org/10.1007/s12284-009-9022-2

- Landen, R. G. (1970). SYLLABUS: HISTORY OF THE MEDIEVAL MIDDLE EAST: A.D. 622-1799. Middle East Studies Association Bulletin, 4(3), 16–54. http://www.jstor.org/stable/45154777

- Millo, L. (1992). Arrroz. El Pais Aguilar.

- Potrykus, I. (2001). Golden Rice and Beyond. Plant Physiology, 125(3), 1157–1161. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4279741

Websites:

- The Moors. Black History School. https://blackhistory.school/the-moors/

- (2021, July 3). Philippines becomes first country to approve nutrient-enriched “Golden Rice” for planting. International Rice Research Institute. https://www.irri.org/news-and-events/news/philippines-becomes-first-country-approve-nutrient-enriched-golden-rice

- Historia Del Cultivo. Arròs de València. https://www.arrozdevalencia.org/historia-del-cultivo-del-arroz/

- Baranski, Marci (2013, September 17). Golden Rice. The Embryo Project Encyclopedia. https://embryo.asu.edu/pages/golden-rice

- Booth, Michael. (2017, October 20). Grains of truth: Why rice is the world’s best-loved staple. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2017/oct/20/rice-japanese-cuisine-meaning-of-rice-michael-booth

- Cuñat, Jose. (2020, December 13). La paella en las culturas culinarias españolas y francesas (siglos xIx-xxI). Locos por la Paella. https://locosxlapaella.com/la-paella-en-las-culturas-culinarias-espanolas-y-francesas-siglos-xix-xxi/

- Duhart, Frédéric y Xavier Medina, F (2021, May 7). La paella: Historia del plato español más famoso. Panorama Cultural. https://panoramacultural.com.co/gastronomia/7953/la-paella-historia-del-plato-espanol-mas-famoso

- Drew, Keith. (2022, February 22). Spain’s ingenious water maze. BBC. https://www.bbc.com/travel/article/20220220-valencias-la-huerta-spains-ingenious-water-maze

- Gokun Silver, Margarita. (2015, October 15). Drink in History at the World’s Oldest Court. Smithsonian Magazine. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/travel/drink-history-world-oldest-court-180956951/

- Hiên, N. X., Liên, T. T. G., & Luong, H. (2004). Rice in the Life of the Vietnamese Tháy and Their Folk Literature. Anthropos, 99(1), 111–141. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40466309

- Kinver, Mark. (2011, March 4). Flood-resistant rice ‘also has drought-proof trait’. BBC. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/science-environment-12636902

- Piqueras, Isabel. (2014, January 5). Arroz y paludismo en la Valencia del siglo XVIII. Historia de Valencia s.XVIII. https://blogs.ua.es/historiavalencia18/2014/01/05/arroz-y-paludismo-en-la-valencia-del-siglo-xviii/