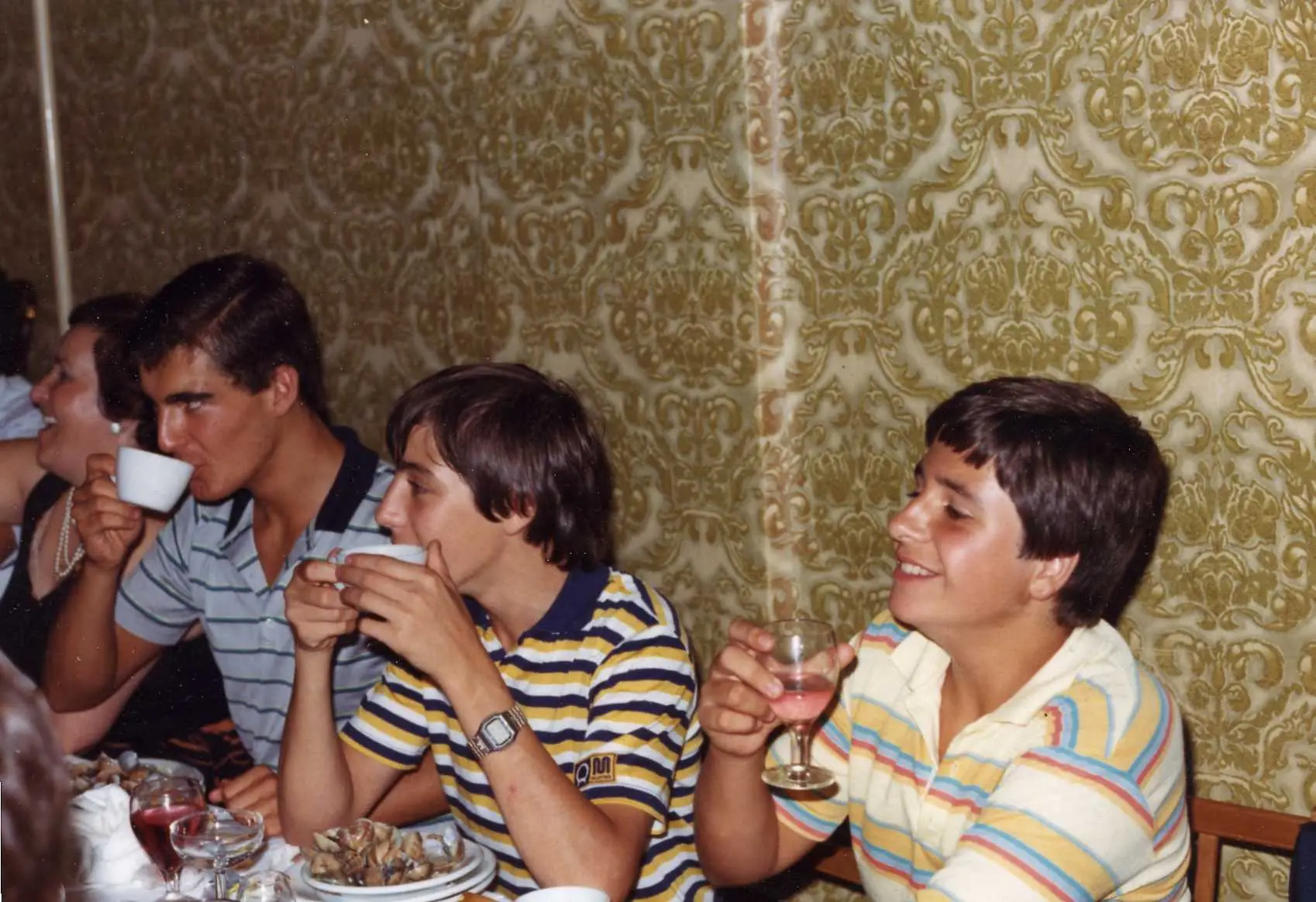

Walking down a road in the heart of Mumbai along with a friend, I found myself surrounded by rows of street vendors and tiny hole-in-the-wall food joints one evening in the middle of June. Navigating through the maze of shops and stalls, a boundless barrage of elbow shoves and foot stampings assured us that the rest of Mumbai had joined in on our visit to Mohammad Ali Road. Contributing to the cacophony, shopkeepers and food vendors bellowed to the limits of their lung capacity, trying to attract each other’s customers. A typical scene in an iconic Mumbai location, championed by the city’s Muslim community during the holy month of Ramzan.

This traffic-laden road transformed into a mecca of street food each evening, as people broke their ritualistic fasts. Stalls showcased sinfully meaty delicacies like kebabs, curries, and rice preparations. It is a confirmed myth that one can find their way onto the road by simply sniffing the delicious air. Aromas of heavy spices, fennel, chilli powder, turmeric, rosewater, saffron, and mint wafted for miles. One could find all sorts of meats being prepared in every delicious possible manner – fried, braised in spices, deep fried, grilled over charcoal, and even seared over a large iron griddle, known as a Tawa. Chicken, buffalo, and mutton preparations were visible on large metal skewers through windows. I would (very soon) discover that it wasn’t just regular meat, but a large selection of offal and other “non-desirable” cuts of the animal.

Offal or variety meat is used to define the viscera and/or the entrails of a butchered animal. The practice of eating offal is quite commonplace in many cultures and countries across the globe. The practice also extends through different time periods. Somewhere along the way though, the practice of eating it in America dwindled. Meat consumption in America today consists largely of the muscle of an animal. If we exclude sausages (which a large segment would not consider offal, though I argue it is), there is an extremely limited inclination to its daily consumption. A stark contrast from a large number of cultures across the world.

Only about 44% of the live weight of a cow makes it to American markets as prime cuts (steaks, ribs, and roasts found in stores) and an additional 12% of carcasses consist of the offal that falls into the by-product gap. The vast majority of organs that account for this 12% are not consumed in the United States but are instead exported to other countries. Edible offal accounts for more than 23% of beef exports (and over 35% by volume of veal exports), according to the 2011 USDA report1.

The very etymology of “offal” seems to jab at its undesirability. The word is derived from the Middle Dutch terms “Af” meaning “off” and “vallen” meaning “to fall”, suggesting it was used to describe the fallen or leftover pieces of the animal during the butchering process2. The stigma against offal consumption also seems to have several racist and classist connotations, with numerous stories of slaves and “the poor” needing to use every edible bit of the discarded entrails and carcass of the livestock after the choice cuts were consumed. In 1943, Life magazine tried to push a rebrand of offal as “variety meat”, a seemingly unsuccessful attempt. The lack of offal consumption was also attributed to the aftermath of the second world war, where America became a rich country with ample space to grow cattle and livestock. This enabled the population easy and cheap access to prime cuts of muscle and over time, with the growth of this meat industry, the need for organ meat eventually diminished3. TV shows like Andrew Zimmerman’s Bizarre Foods only seem to reinforce the notion of these foods being weird and one-off culinary eccentricities.

Circling back to our evening at Mohammad Ali Road, my friend had pre-ordered several popular dishes. He was quick to assure the safety of the experience (way to not see the red flag right?). After a short wait, the dishes made their way to our table. We dug in, and about halfway through the meal, the curtain was dropped. I wasn’t aware of the fact that I was eating organ meat, something I had been reluctant to eat before. Following a momentary shock, there seemed to be no reason to complain and nothing could stop me from licking the plates clean.

We gorged on Gurda-Kaleji; Kidney & liver (respectively) pieces marinated in each purveyor’s choice of spices and seared over an iron griddle, till it got a nice char and a perfect chewy texture. Another dish was Bheja Fry, a semi-dry preparation of goat brains cooked in a spice paste made of chopped onions, tomatoes, and spices, finished with fresh coriander and lime juice along with fresh pieces of bread: the paper-thin Roomali Roti, and Paav, a local bun.

While offal consumption is still a debatable subject in the States, most other cultures around the world have already integrated them into their cultural diets; often due to famine and lack of resources as they were developing. Close to America, Mexico as well as many South American countries use organ meats. Cow udders in Ubre Asada from Argentina, tripe in Guatitas from Ecuador, and Tripas or Machitos from Mexico are prime examples. A similar thread is seen in Asian countries, with the consumption of organ meat happening in daily meals. From Singapore’s iconic Fish Head Curry, Hong Kong’s multitude of preparations starring chicken feet, Tripe and Noodle Soup in Taiwan, Ulo in the Philippines, Yakitori in Japan, to braised tongue in Sichuan cuisine – we see a trend. Tripe, caul, brain, feet, eyes, heads. Anything that can be eaten will be eaten, without any prejudice. Europe eats forms of organ meat too; Frikandel in the Netherlands, Haggis in Scotland, Oxtail Stew in England. The French have taken a further step, incorporating them into haute cuisine. Though daily consumption might not happen, it has roots in the notion of reducing waste and utilising everything that is edible.

In an era of sustainability-driven changes, it is essential to push for cleaner consumption. While the current state of the meat industry is straining the US economy, ruining the farmers, endangering the people eating meat, and using far too much energy, a little efficiency may help – including a change in culture in ways that allow for better utilisation of each individual food animal4. The only other obstacle holding us back is that mental block. Take it from me, a person who normally would usually turn his snout up at the mention of the liver, that a little spice and care is all it would take for someone to consider the offal in their diet.

References

- Marti, Daniel L., Rachel J. Johnson, and Kenneth H. Mathews, Jr. “Where’s the (Not) Meat?: By-products from Beef and Pork Production.” USDA: A Report from the Economic Research Service (November 2011) LDP-M-209-01. As cited by Young, Jake. “The Offal Truth.” Gastronomica 18, no. 1 (2018): 76-82.

- Young, Jake. “The Offal Truth.” Gastronomica 18, no. 1 (2018): 76-82.

- Adams, Cecil. “Why Don’t Americans Eat More Offal?”. September 7, 2016. https://www.washingtoncitypaper.com/columns/straight-dope/article/20833229/why-dont-americans-eat-more-offal

- Zivkovic, Bora. “Offal Is Good.” Scientific American Blog Network. Scientific American, August 10, 2011. https://blogs.scientificamerican.com/a-blog-around-the-clock/offal-is-good/